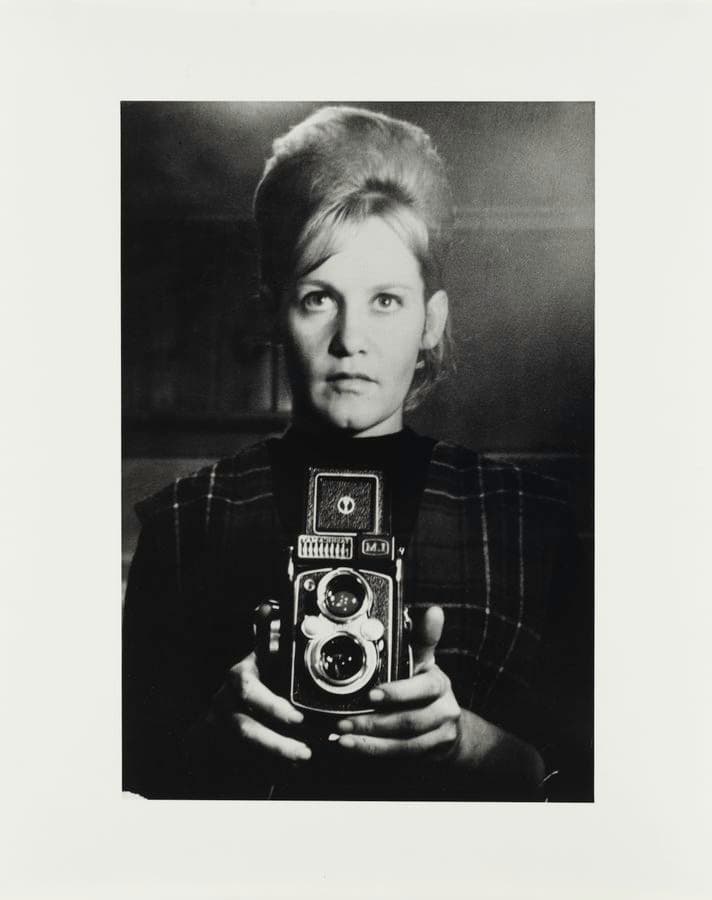

Sue Ford

1943 — 2009“For sometime I have been thinking about the camera itself. Trying to explore its particular UNIQUENESS, coming to terms with the fact that I had been trying to ignore for some years, that the camera is actually a MACHINE … In ‘Time Series’ I tried to use the camera as objectively as possible. It was a time machine. For me it was an amazing experience. It wasn’t until I placed the photograph of the younger face beside the recent photograph that I could fully appreciate the change. The camera showed me with absolute clarity, something I could only just perceive with my naked eye.” — Sue Ford, 1974.

Biography

Sue Ford was among the first feminist photographers in Australia, embarking on a practice in photography and film in the early 1960s. Ford studied photography at RMIT in 1961, where she was one of two women students in an otherwise male cohort. Ford spent only a year at RMIT, quickly tiring of the misogynist nature of its teaching and darkroom culture. She and her friend and fellow photographer, Annette Stevens, established a small commercial studio in Little Collins Street, which ran until 1967. There, Ford made portraits of her friends that were later published in the book A sixtieth of a second 1987.

Ford undertook postgraduate study at the Victorian College of the Arts from 1973 to 1974. This study led to an engagement with conceptual art and an interest in impermanence and the passage of time – a theme that would characterise her subsequent work. She exhibited Time recedes and Metamorphoses in 1971. She a became the first Australian photographer to be given a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1974, showing Time series, a work comprising double portraits of her friends, each taken a decade apart. This work is a cornerstones of avant-garde and conceptual photography in Australia.

Ford’s practice was deeply informed by her feminist views: she actively resisted her work as being in any way technologically refined or precious, or ruled by any particular hierarchy. She was also an active participant in feminist film co-operatives as a member of the Feminist Film Workers collective in the 1970s and 1980s, Reel Women from 1979 to 1983 and the Women’s Film Unit in 1984–1985. She made a number of radical short films through 1970s and 1980s including Faces, Time changes and Egami, and went on to experiment with innovative digital printing technologies in the early 1990s, including photocopy and laser printing. In the 1980s, Ford engaged with questions of Australian identity, exploring Indigenous politics and colonial history. In 1988 she taught photography to Tiwi women on Bathurst Island and photographed the negotiations for self-determination between senior Aboriginal lawmen and the Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, at the Barunga Festival near Katherine. She regarded her photographs of Aboriginal women dancing at the festival as the most important of her career.

In her later years Ford returned to questions of her own history and biography, producing a photographic series based on her grandfather’s WWI experiences in 1999. Her final work was the Self-portrait with camera, an extended autobiographical series consisting of 47 self-portraits taken throughout the course of her life. Ford died of cancer in Melbourne in 2009. In 2004 she had received Australia Council funding to catalogue her photographic archive, a task that has since been continued 2010 by Joy Hirst and her son, Ben Ford. There have been several significant exhibitions of Ford’s work, including solo exhibitions held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1982 and at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1988, 1994 and 2014.

Biography written and edited by Dr Nicola Teffer in collaboration with NGA curatorial and research staff

Sue Ford, Faces, 1976, purchased 1984

Sue Ford, Self portrait, Brighton, Melbourne, 1961, purchased 1983 © Sue Ford/Copyright Agency

//know-my-name/media/dd/images/64184.ba24299.jpg)